Bulletin 74-81 Introduction

If our groundwater supplies are to remain useful to us, we are obligated to protect their quality. It is ironic that one way in which groundwater quality can decline is through the well. This occurs when, because of inadequate construction, wells provide a physical connection between sources of pollution and usable water. The geologic environment has some natural defenses against pollutants, but each time we penetrate that environment, we may carelessly establish avenues for their uncontrolled introduction. Abandoned wells pose a particularly serious threat, not only to groundwater quality, but also to the safety of humans, especially children, and to animals. Such wells are frequently and conveniently forgotten and once out of mind, there is little chance of preventing them from eventually becoming a problem.

The potential for such problems is growing because the number of wells is increasing. Around 15,000 new wells are constructed each year. In 1977, at the height of the 1976-77 drought, an estimated 28,000 wells (about double an average year) were drilled in the State. The number of wells abandoned each year is not known.

A properly constructed or adequately destroyed well should maintain, as far as practicable, those subsurface conditions which, prior to construction of the well, prevented the entrance of unsanitary and inferior-quality water into usable groundwater supplies. Standards for the construction of water wells and for the destruction of so-called "abandoned" wells can be a significant factor in the protection of groundwater quality and should contribute to the betterment of the health and welfare of the people of the State.

Impairment of the quality of groundwater of the State through improper construction or abandonment of wells has long been one of the concerns of the Legislature. In 1949 it enacted legislation which, among other matters, directed the Department of Public Works to investigate and survey conditions of damage to quality of underground water caused by improperly constructed, abandoned or defective wells and to report to the appropriate Regional Water Pollution Control Board its recommendations for minimum standards of well construction (Chapter 1552, Statutes of 1949). These investigative and reporting responsibilities are now lodged in the Department of Water Resources by Water Code Section 231, which reads as follows:

231. The Department, either independently or in cooperation with any person or any county, state, federal or other agency, shall investigate and survey conditions of damage to quality of underground waters, which conditions are or may be caused by improperly constructed, abandoned or defective wells through the interconnection of strata or the introduction of surface waters into underground waters. The Department shall report to the appropriate California Regional Water Quality Control Board its recommendations for minimum standards of well construction in any particular locality in which it deems regulation necessary to protection of quality of underground water, and shall report to the Legislature from time to time, its recommendations for proper sealing of abandoned wells.

During the 1965 and 1967 General Sessions, the Legislature again reviewed the matter of standards for water well construction. As a result, it established a procedure for implementing standards developed under Section 231 by enacting Chapter 323, Statutes of 1967, which added Sections 13800 through 13806 to the Water Code. The wording of these sections was amended in 1969 when the Legislature enacted the Porter-Cologne Water Quality Control Act (Chapter 482, Statutes of 1969). In Section 13800, the Department of Water Resources' reporting responsibility is enlarged upon:

13800. The Department, after such studies and investigation pursuant to Section 231 as it finds necessary, on determining that water well and cathodic protection well construction, maintenance, abandonment, and destruction standards are needed in an area to protect the quality of water used or which may be used for any beneficial use, shall so report to the appropriate Regional Water Quality Control Board and to the State Department of Health Services. The report shall contain such recommended standards for water well and cathodic protection well construction, maintenance, abandonment, and destruction as, in the Department's opinion, are necessary to protect the quality of any affected water.

The State Department of Health Services also has a concurrent interest in problems caused by improperly constructed, defective, or "abandoned" wells. This interest is evidenced in the "California Safe Drinking Water Act" (Chapter 7 of Part 1 of Division 5 of the Health Safety Code, State of California), which deals with the health aspects of public water supplies. Under this authorization, the Department of Health Services requires a water purveyor to apply for an amended water permit before a new well is constructed and connected to the water system. Before the amended (or new) permit is issued, a thorough review is made of (a) the location of the well with respect to potential contamination hazards, (b) design and construction of the well necessary to prevent contamination or the exclusion of undesirable water, and (c) the bacterial and chemical quality of the water produced. The Department may issue a permit if it finds that the water "under all circumstances is pure, wholesome, and potable and does not endanger the lives or health of human beings." Specific water quality and monitoring standards have been adopted by regulation. If at any time water produced from an existing well fails to comply with such standards, the Department may require changes or modifications of the well, provisions of appropriate water treatment, or cause the curtailed use, even destruction of the well, in order to assure a safe supply to the public.

In summary, the responsibility of the Department of Water Resources is to advise the Legislature and appropriate state agencies on the maintenance of groundwater quality, including protection against adverse effects caused by improper well construction or the abandonment of wells. This responsibility applies to all wells, irrespective of purpose. The responsibility of the Department of Health Services is to investigate, evaluate, and approve public water supplies including the design and construction of water wells.

This report was prepared by the Department of Water Resources in fulfillment of its responsibilities under the provisions of Section 231 of the Water Code, and in cooperation with the State Department of Health Services.

Wells themselves do not cause groundwater quality to deteriorate. Rather, it is inadequate construction, or, in the case of wells that no longer serve a useful purpose, their improper destruction, that can result in the deterioration of groundwater quality. Depending on the circumstances, such quality deterioration may affect the water supplying a single well, or if the pollution is substantial, a sizable segment of a groundwater basin.

The impairment of water quality in an individual well, or group of wells, is the most common. Groundwater supplies have been responsible for a sizable portion of the water-borne disease outbreaks reported in the United States. Most of these outbreaks occurred where wells were so poorly constructed that they allowed contaminants to enter the well. Contaminants entering improperly constructed wells are not limited to disease organisms. There is also a growing number of case histories concerning undesirable chemicals, both toxic and nontoxic, that have gained access to groundwater and adversely affected wells a short distance away.

The mechanism of water quality impairment caused by faulty wells affecting large segments of a groundwater basin is not well defined. In most instances, a number of factors have been involved; the wells have served primarily to facilitate the impairment. The most noteworthy examples in California of widespread water quality deterioration are in coastal groundwater basins that have been subjected to seawater intrusion.

Inadequately constructed or improperly "abandoned" wells are not the sole cause of water quality degradation in a California groundwater basin. A small quantity of contaminants entering one well may not have far-reaching effect. However, (1) the construction of thousands of new wells in California each year, (2) the fact that many are becoming more closely spaced, and (3) the growing number of wells being neglected or indiscriminately abandoned indicate that the potential for impairing groundwater quality is growing. Then, when pollutants move along the lines of natural water movement, the effects will be long-lasting and difficult, if not impossible, to correct.

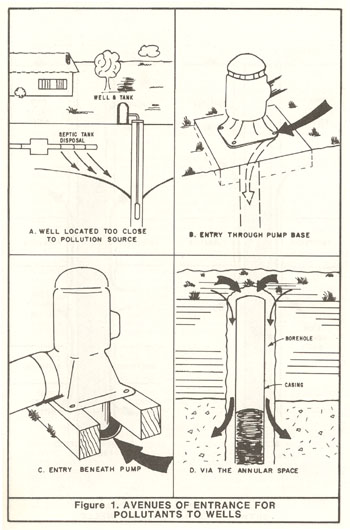

Inadequately constructed or improperly destroyed wells facilitate the impairment of groundwater quality (see Figure 1 and Figure 2) in five principal ways:

- When the well is located too close to sources of pollution or contamination or downstream from them so that the well can be directly affected by flow from these sources (Figure 1A). Ironically, sometimes the source of pollution is a nearby abandoned well.

- When the surface portion of the well is constructed without protective features so that contaminated or polluted waters can flow directly into the well through one or more of several possible openings in or under the pump. Usually under these circumstances only the water in or adjacent to the well is affected (Figure 1B and Figure 1C).

- When the annular space (the space between the outside of the casing and the wall of the hole) lacks an adequate vertical seal and surface water or shallow subsurface water flows into the well along the outside of the casing. (Note that although the annular space may be filled with granular filter material, i.e., the familiar "gravel-pack", no seal exists and undesirable water can move downward or laterally.) This type of defective well is particularly susceptible (Figure 1D) to contamination.

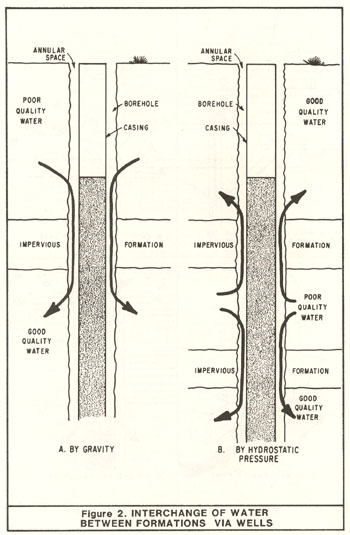

- When, during well construction (or the destruction of abandoned wells), aquifers that produce poor quality water are ineffectively sealed off, allowing the interchange of water with one or more aquifers and thus significantly impairing the quality of water in those aquifers. The well now provides a physical connection between these aquifers (Figure 2).

- When the well is used intentionally, accidentally, or carelessly for the disposal of waste allowing direct contamination of the groundwater to occur. Such disposal is prohibited by law except under specially approved circumstances.

Irrespective of the probability of occurrence and which form of deterioration takes place, wells should be constructed or destroyed such that they do not contribute to the impairment of the quality of California's groundwater supplies. Moreover, while the well construction industry, advisory groups, and regulatory agencies want to protect the quality of the State's groundwater supplies as well as assure that wells are adequately constructed, there is no broad, uniform approach for so doing in California. The resolution of this problem requires the development of standards for water well construction and destruction that will ensure the protection of the State's groundwater as they exist in the ground or as they pass through the well for use. Such standards should be capable of execution by the average competent well driller using commercially available equipment and materials, without imposing undue financial burden on the well owner.

Well standards do more than protect the quality of the groundwater resource; they also provide a degree of consumer protection. When standards are established and implemented in an area, well owners have more assurance that their wells will be constructed properly. Proper construction could mean less maintenance with an extended well life. Most well owners do not realize that deficiencies in design and construction (including failure to close-off access to pollutants described above) are likely to result in higher operating and maintenance costs.

A subject touched upon earlier is the safety hazard posed by the unused or "abandoned" well. While safety is not a matter involving the maintenance of groundwater quality, it should be a concern to all those involved with water wells. Any abandoned excavation is a threat to the safety of people, especially children and animals. Further, State law (Section 24400 of the California Health and Safety Code) requires that abandoned excavations be fenced, covered, or filled. Yet, children (and sometimes adults) and livestock do fall into abandoned wells and other excavations.

By properly destroying abandoned wells, we can easily eliminate this safety hazard.

Figure 1. Avenues of Entrance for Pollutants to Wells

Figure 2. Interchange of Water Between Formations via Wells

Developing the Standards

The Department of Water Resources began formulating standards for the construction of water wells and the destruction of abandoned wells shortly after the enactment of Water Code Section 231 in 1949. The Department made a comprehensive survey of existing laws and regulations governing well construction and abandonment in the then 47 other states and in the counties and cities of California. This survey culminated in the publication of "Water Quality Investigations Report No. 9 - Abstracts of Laws and Recommendations Concerning Water Well Construction and Sealing in the United States", April 1955. Although the report is over 25 years old, it remains a useful source of background information. The Department has continued to keep informed of practices in other states, particularly those in which standards have been established, and changes in the status of California county well ordinances.

Concurrently the Department assembled and evaluated information on the development of well standards in California. The information was grouped into three broad categories: (1) groundwater geology and hydrology, (2) Impairment of groundwater quality, and (3) water well construction practices. The latter included suggestions and recommendations on methods and materials from representatives of State and federal agencies, steel companies, casing fabricators, pump manufacturers, water well drilling contractors, and other organizations and individuals concerned with the development and use of groundwater.

This activity culminated in the publication of the standards in their initial draft form, "Recommended Minimum Well Construction and Sealing Standards for Protection of Groundwater Quality State of California", Bulletin 74, Preliminary Edition, July 1962. In March and April 1965, the Department conducted a series of public hearings in conjunction with the Department of Health Services at six cities in the State. Discussion and comments received centered on two areas: (1) the standards recommended, and (2) means of implementation. Most of those concerned felt that the standards, as written, were too general. Accordingly, the Department decided to redraft them.

Following a review of all prior material and comments received during the period 1963 through 1966, the Department published an interim edition of the standards in February 1967. Two public hearings on the interim edition were held in May 1967, and written comments were received as part of the record. These were also joint hearings with the Department of Health Services.

The eight hearings produced correspondence and an extensive file of transcripts containing information, opinions, and suggestions, which would fill several volumes, if published.

In February 1968 the standards were issued in their current form.

For the most part, the standards can be applied anywhere in the State under practically any conditions. The procedures for closing-off the avenues of access, properly locating a well, destroying an abandoned well, etc., in Del Norte County, at the northwest corner of California, are similar to those in western Fresno County. Similarly, sealing-off the water in one or more zones or aquifers, to prevent its migration to other zones or aquifers, may be just as desirable for a well in western Merced County as it is at one on the Oxnard plain of Ventura County although, perhaps, for different reasons. However, in specific areas of the State it has been necessary to define the existing geologic and hydrologic conditions and the circumstances under which these standards should be applied. For example, it is helpful to describe the areal and vertical extent of geologic materials where sealing is needed to prevent the migration of poor quality water.

Thus, the Department maintained a concurrent and subsequent activity consisting of studies and reports describing the application of standards in designated areas of California. And, in addition to Bulletin 74, the Department issued a number of reports containing well standards for those areas (see Table 1).

One other report, Bulletin 74-1, "Cathodic Protection Well Standards: State of California", March 1973 deals with another kind of well. Cathodic protection wells house devices used to alleviate electrolytic corrosion of pipelines, tanks, and similar installations. Such wells may also function as instruments for the deterioration of groundwater quality. For that reason, standards for their construction and destruction have also been issued.

Table 1 Reports Issued Under Water Well Standards Program

(listed by DWR Bulletin number)

|

Area of Study |

DWR Bulletin Number |

Publication Date1, 2 |

|

Mendocino County |

62 |

November 1958 |

|

Alameda County |

74-2 |

P.E. December 1962 |

|

Del Norte County |

74-3 |

P.E. March 1964 |

|

Central, Hollywood, and |

74-4 |

October 1965 |

|

San Joaquin |

74-5 |

March 1965 |

|

Fresno County |

74-6 |

September 1968 |

|

Arroyo Grande Basin |

74-7 |

July 1971 |

|

Shasta County |

74-8 |

August 1968 |

|

Ventura County |

74-9 |

August 1968 |

|

West Coast Basin |

107 |

August 1962 |

|

Coachella Valley Area |

Unnumbered4 |

August 1979 |

Notes for Table 1:

1. Publications issued prior to June 1971 are out-of-print. Copies may be inspected at Department's district offices, county offices administering well ordinances, and local libraries.

2. P.E. - Preliminary Edition; F.E. - Final Edition.

3. Following the enactment of Sections 13800 through 13806 of the Water Code in 1967 supplemental memoranda reports summarizing the material presented in these publications and recommending the establishment of standards in these areas were issued.

4. Unnumbered memorandum report.

The foreword to the 1968 edition stated that:

"Whereas the standards in this report are as final as they can be at the present time, the Department will revise them from time to time. We recognize that, as with other published standards, to be effective and useful they must be revised and updated in light of both changes in practice and degree of success achieved in their application."

Sufficient changes in the field of water well construction and experience with applying the 1968 standards warrant revising them. Foremost among the changes in construction practices are:

- The development and use of plastic materials for casing in water wells. A subject only alluded to in the 1968 edition, the use of plastic well casing and screen has had phenomenal growth in the United States. So much has the usage increased that a national materials standard has been developed and a manual of installation practices has just been published.

- The use of the air rotary drilling method for constructing wells in the hard rock areas of the State. Although this method of drilling was in use in 1968, its use has mushroomed since then. The equipment is very effective and very fast. Coupled with the use of plastic well casing, the method has made the construction of a well several hundred feet deep in one day a common event in hard rock areas.

- Rapid growth in the use of well screens in place of perforated casing in the intake sections of the wells.

- Increased use of the reverse-circulation method of well drilling for large diameter deep wells in unconsolidated formations. It too is an extremely fast method.

Other factors include:

- Population growth in the hilly and mountainous rural areas of California, which has resulted in a heavy demand for individual and community water supplies in those areas.

- The 1976-77 drought, the most severe in a half-century, which caused a heavy demand for new wells, replacement wells, and well deepenings. It also produced an increased awareness of the significance of the State's groundwater resources.

- The increasing cost of energy for pumping. In terms of well construction and operation, this has meant greater interest in the design of efficient wells and in well maintenance (previously, a much neglected activity).

These as well as other considerations led to the decision to revise the 1968 edition.

This edition is composed of this Introduction, "Standards", and five appendixes.

While there have been a number of modifications and additions to them, the 23 sections of "Standards" are as listed in the 1968 edition. All references to existing laws, standards, and publications have been updated and, where appropriate, additional explanation is provided. Every effort has been made to clarify wording to ensure its understanding. A number of figures illustrating the standards have been included.

Many technical terms concerning groundwater and water well construction are frequently misunderstood or misinterpreted. The term "seal" or "sealing", for example, has several meanings in the jargon of the well driller, geologist, and engineer, depending on what part of the well installation is under discussion. In this report, we have tried to ensure that the technical terms used are understandable.

A list of definitions appears in Appendix A. Certain definitions are made a part of the standards. Appendix B, Appendix C, and Appendix D describe sealing methods, disinfection, and water quality sampling respectively.

Numerous publications relating to the construction of water wells and to the development, use, and protection of groundwaters have been reviewed in preparation of this report. Included is a considerable body of literature on well construction that has been written since 1968. They are listed in Appendix E in alphabetical order by author.

Establishing and Enforcing Standards

Authority for establishing and enforcing standards for construction and destruction of water wells has always rested with the 58 counties and 429 cities in California.

Where public water supplies are concerned, additional requirements may be prescribed by the Department of Health Services. Prior to the release of the 1968 edition of this report, only three counties and a few cities had adopted ordinances regulating the construction of water wells. In 1967, legislation was enacted authorizing the State (through the California Regional Water Quality Control Boards) to require cities and counties to adopt satisfactory ordinances governing well standards in critical areas. If they did not, the State would adopt such ordinances for the cities and counties. (This procedure is outlined in Sections 13800 through 13806 of the Water Code.)

Today, 33 counties have well ordinances establishing standards for the construction of all wells within their boundaries. They are listed in Table 2. Six other counties have adopted ordinances that deal with specific kinds of wells or conditions (as, for example, individual domestic wells only). While this latter group of ordinances provides protection for the users of water from the specified wells in these areas, they do little to protect the quality of the groundwater resource (in contrast with the 33 counties listed in Table 2). Table 3 lists the six counties with ordinances for specific kinds of wells. Thirty-four of the total of 39 county ordinances specify the standards presented in the 1968 edition, with modifications where appropriate (all of which are more stringent than those in the 1968 edition).

Table 2 County Ordinances in California Concerning the Construction and Destruction of Wells (as of December 1981)

|

County |

Ordinance |

Date |

Remarks |

|

Alameda |

73-68 |

7/17/73 |

|

|

Butte |

1845 |

8/2/58 |

|

|

Contra Costa |

1189 |

1/14/58 |

|

|

Del Norte |

73-90 |

11/12/73 |

|

|

Fresno |

470-A-39 |

10/22/74 |

|

|

Humboldt |

897 |

12/21/72 |

|

|

Inyo |

309 |

10/4/76 |

|

|

Kings |

365 |

1/13/76 |

|

|

Los Angeles |

10075 |

9/1/70 |

|

|

Madera |

412 |

3/16/76 |

|

|

Mariposa |

373 |

9/18/73 |

|

|

Mendocino |

1135 |

8/28/73 |

|

|

Merced |

752 |

6/10/75 |

|

|

Mono |

75-459 |

8/26/75 |

|

|

Monterey |

1967 |

5/29/73 |

|

|

Napa |

335 |

12/1/70 |

|

|

Orange |

2607 |

7/18/72 |

|

|

Placer |

1498B |

5/9/72 |

Amended 1977, 1981 |

|

Sacramento |

508 |

10/26/55 |

|

|

San Bernardino |

1954 |

10/15/74 |

|

|

San Diego |

4286 |

4/3/74 |

|

|

San Joaquin |

1862 |

12/21/71 |

|

|

San Luis Obispo |

1271 |

5/7/73 |

|

|

San Mateo1 |

2413 |

1/11/77 |

|

|

Santa Barbara |

2769 |

9/29/75 |

|

|

Santa Clara2 |

75-6 |

10/14/75 |

Ordinance of the Santa Clara |

|

Santa Cruz |

1577 |

2/16/71 |

|

|

Shasta |

479 |

6/30/69 |

|

|

Sonoma |

1594 |

12/18/72 |

|

|

Stanislaus |

NS443 |

6/5/73 |

|

|

Tulare |

1758 |

8/13/74 |

Amended 4/16/76 |

|

Ventura |

2372 |

8/31/70 |

Amended 10/1/79 |

|

Yolo |

765 |

9/7/76 |

|

Notes for Table 2:

1. Predecessor ordinance numbers 1100 (12/15/55) and 2324 (7/8/75).

2. Separate ordinance for subdivision wells - NS1203.22 (4/21/64).

Table 3 County Ordinances in California with Limited Application to Wells (as of December 1981)

|

County |

Ordinance |

Date |

Application |

|

Kern |

G1225 G3321 |

12/16/69 9/21/81 |

Community water supply wells |

|

Marin |

1463 |

1965 |

Domestic water supply |

|

Plumas |

786 |

5/15/73 |

Domestic wells only |

|

Riverside |

340A |

5/3/481 |

Provisions concern permit |

|

San Francisco |

659 |

1952 |

Individual domestic wells only |

|

Sierra |

420 |

5/7/74 |

Well construction only |

Notes for Table 3:

1. Amended December 1, 1952, and December 23, 1957.

One-third of the 429 cities in California have also adopted well ordinances. Many cities have working arrangements or agreements with county governments, so it is difficult to state the exact number of cities employing well construction standards.

Cities with ordinances are situated in the following counties (number of cities with ordinances in parenthesis):

Alameda (4)

Fresno (8)

Kern (1)

Los Angeles (51)

Merced (3)

Nevada (1)

Orange (26)

Placer (1)

Riverside (1)

Sacramento (1)

San Bernardino (1)

San Diego (10)

1

San Joaquin (6)

San Luis Obispo (6)

San Mateo (5)

Santa Barbara (2)

Stanislaus (1)

Sutter (1)

Ventura (9)

Note regarding the number of cities in San Diego with ordinances:

1. Since it has no groundwater resource, the eleventh city in San Diego County, Coronado, has no ordinance.

Design and Performance Guidelines

While the standards presented here are designed to protect the continued utility of the State's groundwater resources, they are only incidentally related to the effective use of these resources. Events of the past decade have emphasized the need for conservation of water and energy. Furthermore, consumers (in this case, well owners) have become more aware of problems resulting from inefficient operation (as reflected in increased energy consumption) and inadequate maintenance.

Accordingly, this section was prepared to provide well owners and drillers with guidelines for measuring performance that will lead to the design and construction of more efficient wells as well as those requiring less maintenance.

Testing for Capacity

Every well owner is interested in how much water the well will produce and how dependable the production will be with time. To make that determination a capacity test or performance test must be made. Usually this involves installing a pump and operating it at the expected production rate over a certain length of time. There is considerable variation in actual practice on how such tests are performed depending on the dimensions of the well, including expected capacity and intended use as well as geologic conditions at the site. Obviously, for a small capacity well, i.e., one that produces under 50 gallons per minute, the test would not be as elaborate as it would be for a high capacity well, but is no less important.

The amount of water needed is determined by the intended use of the water. For example, on the average, each person in a household uses 100 gallons of water a day. To the daily household use must be added seasonal uses such a lawn and garden irrigation, swimming pools, etc. Table 4 lists the volume of water supplied from a small capacity well, assuming continuous pumping for 24 hours. Thus, a well supplying one to three gallons per minute is a reasonable amount for a single family dwelling. Additional amounts, such as for watering livestock or irrigating small acreages of crops, must be added to these values. Table 4 also indicates that a family of four could subsist on the water supplied by a well pumping constantly at the rate of only one-quarter gallon per minute. Unfortunately, at this rate there is little margin for error.

Table 4 Volume of Water Pumped Continuously from Small

Capacity Wells

|

Pumping Rate |

Total Pumped in 24 Hours (gallons) |

|

0.25 |

360 |

|

0.5 |

720 |

|

1 |

1,440 |

|

2 |

2,900 |

|

3 |

4,300 |

|

5 |

7,200 |

|

10 |

14,400 |

|

50 |

72,000 |

Small Capacity Wells. Performance tests for small capacity wells are relatively simple. A widely used test for small capacity wells is a pump test which lasts for four hours or until an apparently stable pumping level has been achieved at a rate equal to that expected for the permanent pump. However, in the hilly and mountainous "hard rock" areas of the State there are no defined aquifers and supplies are related to fracture patterns, the nature and extent of the soil mantle, faults, changes in stratigraphy, etc. In such areas the production potential of a well cannot be accurately assessed. Further, wells in these areas often exhibit a satisfactory initial production, which then declines due to poor recharge characteristics of the surrounding material. In such situations a longer than usual test, upwards of 12 to 24 hours (and longer) duration, may be desirable.

Bailing or air-blow tests give an approximate indication of production. They do not provide information of the accuracy needed to determine well capacity or to design an efficient pump system. (Air lift testing differs from air-blow testing. It involves pumping with air, not blowing the water out of the well as is the case with the air-blow test.)

The ability of the water level in a small capacity well to recover should be observed. If the water level fails to return to nearly its original level after 24-hours, the reliability of the producing zone is open to question.

Large Capacity Wells. Where large capacity wells are concerned, capacity tests are more elaborate and extensive. Such wells are usually located in defined, productive groundwater basins, where considerable information on existing conditions is normally available to aid in the evaluation of their performance. All should be pump tested; bailer tests are of little value. The test pump should be capable of pumping 125 percent of the desired yield of the well. Pumping should be continued at a uniform rate until the "cone of depression" reflects any boundary condition that could affect the performance of the well. This could be as short as six hours and as long as several days, depending on aquifer characteristics and knowledge of the aquifer(s) in which the well is situated. The discharge rate and drawdown established should be maintained for specified time period. The ratio of the discharge rate to the drawdown is called the specific capacity of the well for that time period. The units for specific capacity are gallons per minute per foot of drawdown. Static water levels must be measured in advance of the test and after the test during recovery.

Detailed descriptions of procedures and methods used in conducting pump tests for large capacity wells and for analyzing and interpreting the results are too lengthy to be included in this publication. Such information will be found in literature on groundwater and on the design of water wells.

Well Efficiency

Well efficiency is defined as the ratio of the theoretical drawdown in the formation to the actual drawdown in the well. The difference between the two is caused by frictional energy losses of the water as it moves from within the formation to the pump intake. Thus, well efficiency describes the effectiveness of a well in yielding water. Well efficiency should not be confused with pumping-plant (motor and pump) or "wire-to-water" efficiency used to measure pumping-plant performance.

It should be obvious that well efficiency is related to the cost of pumping and the use of energy. If efficiency improves, pumping costs and energy consumption will drop. Thus, optimum well design is no less important where a small capacity well is concerned than it is for one with a large capacity. Unfortunately, design and construction practices that produce efficient wells are often sacrificed in order to save on the cost of constructing a well, particularly in the case of small capacity wells. However, the increased cost of design and construction can be offset by decreased maintenance and operating costs over the long run, although it should be recognized that there is a limit to what can be achieved when compared to expenditure. Current design and construction technology is capable of producing wells with efficiencies of 80 to 90 percent. Pumping-plant or "wire-to-water" efficiency is currently at 65-70 percent.

Sanding

Irrespective of size or composition, any loose material entering a well is usually called "sand", and wells that regularly produce significant quantities of loose material are termed "sanders". The continued influx of sand to a well results in damage to pumps and leads eventually to decreased capacity, and thus a reduction in well efficiency. Further, enough sand may pass through the well to create cavities in the aquifer around the intake section of the well. As a result, such cavities can collapse and damage the well casing or screen. While most wells pump a minor amount of sand, excessive sanding is usually caused by poor well design or inadequate development.

Uncased ("Open-bottom") Wells. Casing serves to hold up the walls of the borehole and provide a path for the movement of the water. In formations with material that will not loosen and be carried away by the inflowing water, such as crystalline rock and other "hard rock" formations, the practice is to leave the intake sections uncased. (Theoretically in such instances, well efficiency would be 100 percent.) Unfortunately, in certain areas some drillers believing the underlying material to be fully consolidated or attempting to save on costs, have drilled open-bottom wells that later produced sand. Furthermore, as pumps lowered following declining water levels, such wells developed sanding problems. This occurred in several areas in the Central Valley during the 1976-77 drought. In such instances, the wells should have been completely cased to prevent caving and the intake section screened to prevent the entrance of sand.

Inadequately Designed Intake Sections. Sanding is often the result of poor selection of screen size or perforation dimensions and/or, where used, filter material (the "gravel pack"). The well screen aperture (slot) openings or the perforated section, should be selected to provide sufficient open area to allow the desired quantity of water to enter with minimal friction losses while keeping out 90 to 95 percent of the natural aquifer material or filter material.

Artificial filter materials perform a similar function. In addition to allowing the water to enter the well openings and preventing the entrance of fine-grained material, artificial filters are also used to increase the effective diameter of the well and increase the yield of certain wells by allowing numerous thin aquifers to produce water. On the other hand, they need not be used unless there are conditions that make their use desirable or necessary. Artificial filters are desirable when the aquifer has a "uniformity coefficient" (see Note 1) of less than 2.5 (some authorities recommend a value of less than 3), or in poorly consolidated rock, i.e., rock that tends to cave when pumping occurs.

Detailed information on the design of intake sections, including the selection of well screen aperture openings and artificial filter materials, will be found in most publications dealing with groundwater and water wells, a number of which are listed in Appendix E.

Incomplete Development. Well construction causes compaction of unconsolidated material about the walls of the drilled hole and drilling fluid also invades these walls, forming a mud cake. In consolidated rocks, cuttings, fine particles and mud can be forced into joints and fractures. Thus, the borehole walls become clogged, reducing the potential yield and causing a drawdown to be increased. Proper well development breaks down the compacted walls (or opens fractures) and draws the material into the well where it can be removed. Obviously, the more thorough the development the better the well will perform. Adequacy of development is largely a matter of experience and judgment. The success of development can be measured by the amount of sand produced during interrupted pumping and the final specific capacity of the well.

Testing for Sand. The sand content should be tested after development and performance (pump) testing. Sand production should be measured by a centrifugal sand sampler (See Note 2) or other acceptable means. Following development (i.e., stabilization of the formation and/or gravel pack) and pump testing, the sand content should not exceed a concentration of 5 ppm (parts per million) by weight 15 minutes after the start of pumping.

Sand production exceeding this limit indicates that the well may not be completely developed or may not have been properly designed. In that event, redevelopment may be appropriate or as an alternative, a sand separator installed. In existing wells should this value be exceeded significantly, rehabilitation (redevelopment) or repair is probably needed. Again, as an alternative, a sand separator may need to be installed.Water Well Drillers' Reports

Detailed and comprehensive knowledge of the occurrence and quality of California's groundwater resources is vital to protecting, conserving, and properly developing them. The data obtained during the construction of water wells are primary sources of geologic and hydrologic information. In 1949 the Legislature concluded that such information would be invaluable in the event of underground pollution, and would provide a fund of geologic information regarding the State's groundwater resources. As a result, legislation was passed requiring the filing of a report with the Department. The report is called the Water Well Drillers' Report and its submittal is also a requirement of these standards (see Section 7 "Reports"). Additional information about the report is presented in “Guide to the Preparation of the Water Well Drillers’ Report,” Department of Water Resources, October 1977.

Comments and Public Hearings on Draft Edition

Where a publication is of general interest or its subject is one on which there can be a diversity of opinion, it is the policy of the Department of Water Resources to issue it in preliminary form and solicit comments from interested organizations and individuals and the general public. Since the standards for the construction of wells and the destruction of abandoned wells recommended herein are for application throughout the State, and because they are specified by many counties and cities (in ordinances or regulations), a draft edition was prepared and distributed for comment (April 14, 1981). In addition, four public hearings or meetings (of an informal nature) were held to obtain the views of persons interested in, or concerned with, the construction and use of water wells. These hearings were conducted in cooperation with the Department of Health Services represented by its Sanitary Engineering Section since this report contains provisions which pertain to the public health aspects of water well construction. The hearings were held during June 1981 at Berkeley, Fresno, Redding, and Los Angeles. In response to a number of requests, the comment period was extended to September 1981.

Fifty-five persons representing 33 individuals and organizations attended the four hearings. Five formal (written) statements were presented and 16 persons commented verbally. In addition, written comments were received from 33 other organizations and individuals. Those submitting written comments are listed in Table 5. Copies of the written comments are available for inspection in the Department's file in Sacramento.

Table 5 Organization Submitting Written Comments on Draft of Bulletin 74-81

|

Organization |

Representative |

Date of Comments |

|

Alameda County Water District |

E. L. Lenahan |

5/19/81 |

|

Associated Drilling Contractors |

D. D. Mickel |

8/7/81 |

|

Associated Drilling Contractors, Tri Counties Branch |

R. L. Strahan |

6/9/81 |

|

Associated Drilling Contractors, Tri Counties Branch |

R. L. Strahan |

9/14/81 |

|

Associated Drilling Contractors |

D. B. Trunnell |

5/20/81 |

|

Ballard & Foote Drilling |

R. H. Foote Jr. |

7/28/81 |

|

Buena Vista Water Storage District |

H. K. Russell |

6/10/81 |

|

C & N Pump and Well Company |

F. Clough |

5/1/81 |

|

California Regional Water Quality Control Board, |

W. S. Johnson |

8/27/81 |

|

California Regional Water Quality Control Board, |

R. M. Hertel |

9/10/81 |

|

California Regional Water Quality Control Board, |

S.R. Ritchie |

5/20/81 |

|

California Regional Water Quality Control Board, |

R. R. Nicklen |

6/8/81 |

|

California Water Service Company |

G. W. Adrian |

8/5/81 |

|

Clark Well & Equipment Company, Inc. |

R. L. Clark |

9/3/81 |

|

Coachella Valley Water District |

L. O. Weeks |

6/8/81 |

|

DeLucchi Well & Pump, Inc. |

J. DeLucchi |

6/25/81 |

|

Dougherty Pump & Drilling |

C. L. Fasnacht |

6/13/81 |

|

Dow Chemical U.S.A. |

J. Jones |

6/11/81 |

|

Fresno County Department of Health |

C. Auernheimer |

6/4/81 |

|

Robert Garcia Well & Pump Company |

R. E. Garcia |

8/28/81 |

|

Harding-Lawson Associates |

F. C. Kresse |

8/28/81 |

|

Richard A. Hendry, Attorney-at-Law |

R. A. Hendry |

6/19/81 |

|

Michael F. Hoover |

M. F. Hoover |

5/20/81 |

|

Los Angeles County Department of Health Services |

N. F. Hauret |

6/10/81 |

|

Luhdorff & Scalmanini |

E. E. Luhdroff Jr. |

6/10/81 |

|

Monterey Co. Flood Control and Water Conservation District |

R. R. Smith |

6/9/81 |

|

Department of the Navy |

W. N. Sorbo |

6/17/81 |

|

Placer County Health Department |

M. A. Winston |

8/28/81 |

|

Santa Clara Valley Water District |

J. L. Richardson |

7/9/81 |

|

Santa Cruz County Environmental Health Services |

L. R. Talley |

5/28/81 |

|

Southern California Water Company |

D. F. Kostas |

8/20/81 |

|

Stanislaus County Department of Environmental Resources |

J. Aud |

6/25/81 |

|

State Water Resources Control Board |

C. Whitney |

6/16/81 |

|

Joseph B. Summers, Civil Engineer, Inc. |

J. B. Summers |

6/5/81 |

|

Joseph B. Summers, Civil Engineer, Inc. |

R. L. Reynolds |

8/28/81 |

|

Tulare Lake Basin Water Storage District 1 |

B. L. Graham |

6/5/81 |

|

Ventura County Environmental Health Department |

D. W. Koepp |

6/8/81 |

|

Ventura County Public Works Agency |

G. J. Nowalk |

8/14/81 |

|

Water Well Surveys |

W. C. Wigley |

6/16/81 |

|

Well Products West, Inc. |

C. Willis |

6/12/81 |

|

Well Products West, Inc. |

C. Willis |

8/4/81 |

|

Woodward-Clyde Consultant |

J. A. Gilman |

6/24/81 |

All comments were carefully reviewed and considered. As might be expected, opinions differed on the applicability of certain standards, guidelines, and procedures. There is, of course, some validity in each point-of-view, which forms the basis for reconsideration. Many comments were incorporated in this final draft. Others were not used for various reasons. Most of the comments dealt mainly with (1) the standards, specifically Sections 1, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 21 and 23; (2) the Design and Performance Guidelines section of this Introduction; and (3) Appendixes B, C and D, which deal with methods and procedures.

Bulletin 74-81 Introduction Notes:

1. The uniformity coefficient is a ratio that describes the variation in grain size of granular aquifer material. It is defined as the ratio of the particle size of a material at which 60 percent of the particles are finer and 40 percent are coarser (called D40) to the "effective" grain size (i.e., the particle size of the material at which ten percent of the particles are finer and 90 percent are coarser (D90). The value of the uniformity coefficient for a material of one grain size is unity; for a heterogenous sand it might be 30.

2. Such a device is described in the Journal of the American Water Works Association, Volume 46, No. 2, February 1954.

Quick Links

- Bulletin 74-81 Introduction

- Bulletin 74-90 Introduction

- Part I. General, Water Well Standards

- Part II. Water Well Construction

- Part III. Destruction of Water Wells

- Monitoring Well Standards, Introduction

- Part I. Monitoring Well Standards, General

- Part II. Monitoring Well Construction

- Part III. Destruction of Monitoring Wells

- Cathodic Protection Well Standards

- Part I. General, Cathodic Protection Well Standards

- Part II. Cathodic Protection Well Construction

- Part III. Destruction of Cathodic Protection Wells

- Appendices